Voice up: Should college athletes be paid?

June 3, 2019

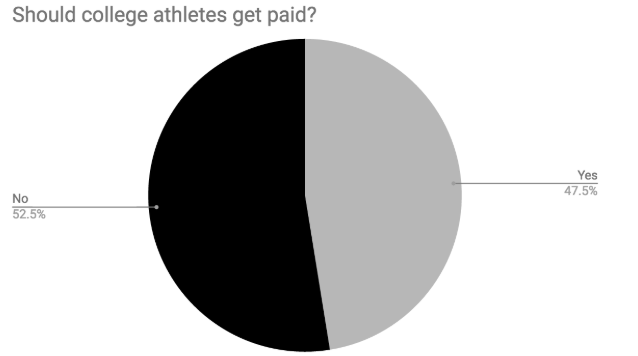

The notion of paying collegiate athletes has been contested and debated for years. Recently, several high-profile cases have once again generated negative headlines. As such, discussions of paying student athletes have proliferated among the popular press, college administrators, players themselves, the general public and sport management scholars.

Should collegiate athletes remain amateurs, or should they be financially compensated for their

Talent? Time to Voice Up.

Athletes deserve the money

Matthew Arena

Being a college student-athlete is a full-time job, bouncing between the weight room, the court/field, classes, and film sessions. College athletics are extracurricular activities, but the schedules of the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) tournaments require an extended period in which the student-athletes must miss school. Not only do they miss class, but they are absent for nationally televised games that make a lot of money and receive millions of viewers.

Since student-athletes also bring in revenue for their team and college or university, especially in the championship games, those who debate in favor of paying them say the students could receive a small portion of the profits. Yes, pay would vary, just as the universities with the more successful teams receive more television time or money than those with less successful teams

College football and men’s basketball programs earn far more than any other athletic program, so these athletes would likely earn more as well. This may not be considered fair pay, but many of those who argue in support of paying college players point out that team popularity and consumers generally determine what is “fair.” These sports also tend to support other less popular sports that do not bring in a lot of money on their own.

Student-athletes are the ones working hard out on the court and field. Coaches might have a big effect on a team, but it is up to the athletes to get it done. Coaches receive bonuses for breaking records, reaching the offseason, and winning the big games; the athletes receive none of it.

Most profits from college athletics do not go towards academics. Instead, they go to the coaches, athletic directors, and some administrators. Student-athletes do not need to receive huge salaries like their coaches; rather, they could still be paid a reasonable amount relative to how much the program makes. Scholarships often cover most of the student-athletes’ books and room expenses, but even few extra hundred dollars per year could compensate for the lack of time these students have to earn spending money at a regular part-time job.

This means offering percentages off of what the team makes in revenue. It is easy to avoid the common counter-argument, “how do you pay some players and not others?” Well it is actually quite simple: teams can offer percentages of total revenue. This means when recruiting a player, Villanova basketball can offer one percent of total revenue which would be thousands of dollars, close to half a million, but then when Villanova football recruits a player, one percent of total revenue is significantly less than the basketball players. This means the athletes playing on a big time program for a popular sport will be getting paid significantly more than a lower level player playing a less popular sport. The constant rate of pay based off revenue is fair for all.

It’s also important to note that college student-athletes are not only a part of a sports team; they are a part of the college or university’s advertising team. For example, the “Flutie effect” is used to describe a surge in college admission following a big sports win. It’s named for Boston College quarterback Doug Flutie; he won the Heisman Trophy in 1984, and the College’s admissions rose significantly in subsequent years—though the extent of Flutie’s impact has been largely refuted by BC officials since then. Still, colleges and universities use their athletic success to promote their school and entice potential applicants.

Student-athletes should be paid for this and all the additional benefits they provide for their schools.

Scholarship is investment by colleges and payment for amateurs

Frank Fishman

These athletes are being awarded free college tuition in exchange for their services. For example, the average annual cost before aid at Duke University is $67,005. In a sense, Zion Williamson earned nearly $70,000 this past season by NOT having to pay that amount to Duke.

Everyone will point to the money colleges and universities make from their athletic programs and claim they exploit their athletes. The profits they make is absorbed, as in March Madness alone, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) pulled in over $900 million in revenue. However, it’s important to understand that athletic programs are investments for schools. For every set of free tuition they hand out, they expect that player to contribute and generate money back to the program. The same logic applies to coaches, professors, and students. The goal of an academic institution is to educate and make money. Making money is not a greedy act by the universities, as everyone benefits. Schools now have additional money to give out in the form of financial aid or philanthropy, as well as further invest in groundbreaking research teams.

Furthermore, scholarships do matter for student-athletes. Fewer than two percent of NCAA student-athletes go on to be professional athletes. In reality, most student-athletes depend on academics to prepare them for life after college. Education is important. There are nearly half a million NCAA student-athletes, and all but a select few will go pro in something other than sports.

While competing in college does require strong time-management skills and some thoughtful planning with academic advisors to work around a hectic athletic schedule, on average NCAA student-athletes graduate at a higher rate than the general student body. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the college graduation rate across all US students was 59 percent in 2018. However, for NCAA Division I student-athletes in 2018, the graduation success rate was 87 percent. It’s not necessarily the intelligence of Division I athletes that make them nearly 30 percent more likely to graduate than the general population. Rather, it’s that there is no financial barrier between them and their degree. Many students are forced to drop out of school, as they simply cannot afford it. But, for a student-athlete, this is not an issue, as most receive some form of financial aid, with many earning a full scholarship. No loans, no working their way through school…just going to class and then to practice or a game.

Basketball is the only sport where the gap between professional and college is remotely close. An argument can be made that talents like Williamson and others belong on the professional hardwood even in their late teens. However, the solution to this does not reside in the NCAA’s hands, but rather the professional circuit. The National Basketball Association (NBA) is currently considering altering its draft eligibility rules, changing the minimum age from 19 to 18. This would allow prospects to enter the draft directly out of high school, and eliminate the “one and done” concept where athletes will only go to college for one year until they are draft eligible. This change, in addition to new leagues offered by the NBA or in Europe, gives young athletes the chance to be professionals and earn real money right away. The financial opportunities are available, so college must be reserved for education, where scholarship is compensation.